930 Shiloh Road, Bldg. 44, Suite E, Windsor, CA, United States of America, 95492

Feeds

Why Is My Yield So Low? Timely Canopy Management Matters

We were recently contacted by a grower distraught over his consistently low yield.

Yield-quantity is a funny thing for producers of quality grapes destined for fine-wine production. Growers love a heavy year but winemakers are weary of over-cropping. Usually on a high-crop year, much of that crop ends up dropped. It’s hard to find that happy medium that satisfies both parties. When what you’re bringing in can’t cover farming costs, that’s a problem for everyone.

The usual suspects...and it's not Kevin Spacey

Shatter or “coulure” (from the French word couler meaning to fall off or leak) brought about by abortion of flowers or ovaries is a typical reason for a light crop. Flowering is a very delicate time during the vintage. If your vines are water-stressed you might find that flowers never set, i.e. turn into berries. If nutrients are out of whack, you might find the same thing. An excess of nitrogen or deficiency of boron or zinc, for instance, can be very detrimental. Sometimes the weather just doesn’t cooperate. A cold rain right at flowering or high winds can mean you end up harvesting individual grapes rather than clusters come the fall.

Some clones of Pinot noir are especially susceptible to shatter. Calera for instance is a notorious low yielder. Oddly enough, we had some of the best fruit set we’ve ever seen for Calera in 2021. My theory (adjusts tin-foil hat) is that this clone is extremely sensitive to excessive nitrogen and the same dry weather that left many vineyards starved for nutrients actually benefited this N-averse clone. That’s my hypothesis anyway.

Going back to the beginning

The grapevine is an awesome plant. One of my favorite things about it is that the yield for each year gets started the spring of the year before. That’s actually a pretty weird phenomenon in the plant world. So really, if you want to get to the bottom of why 2021 didn’t produce much, you want to look all the way back to three months after budbreak of the 2020 season!

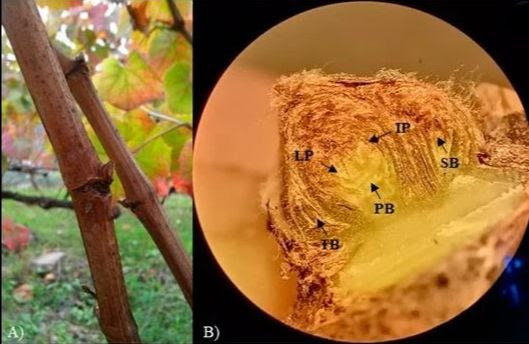

PB, SB, TB: primary, secondary and tertiary bud respectively.

PB, SB, TB: primary, secondary and tertiary bud respectively.

LP: Leaf primordia.

IP: Inflorescence primordia.

You can already get an idea of what your yield is going to look like by looking at your buds over the winter. Remove a bud from a dormant cane, and slice right along the dorsal side (as shown above). Using either a magnifying glass or the naked eye, you can see the little cabbage-looking thing that will one day be the shoot. Look closer and you can see the little smudges that constitute inflorescence primordia: your future clusters.

Read the rest of the post here.

For information on soil moisture probes and other vineyard technologies contact paul@advancedvit.com

About

Advanced Viticulture's principal viticulturist is Mark Greenspan, Ph.D.

Contact

Contact List

| Title | Name | Phone | Extension | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dr. | Mark Greenspan | mark@advancedvit.com | 707-838-3805 |

Location List

| Locations | Address | State | Country | Zip Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced Viticulture, Inc. | 930 Shiloh Road, Bldg. 44, Suite E, Windsor | CA | United States of America | 95492 |